Let us not mince words; Tol Barad is a brutal battleground. It’s not just that the fights are intense – they are – and it’s not just that it heavily favors the defense – it does. No, Tol Barad’s brutality is that it can and will break your faction’s spirit.

We know that attacking Tol Barad is difficult. Truly difficult. The odds are against your assault team. You need more leadership, more communication, and more willpower to take this island than any other PvP objective in the game. Taking Tol Barad is really hard. Keeping it is hard, too.

The obstacles in our way are not trivial, but nor will they stop us. Why do we try to become Kingslayers or reach the gold cap? Why do we chase Insane titles or try for achievements at absurdly low levels?

We do them because they focus our attention, sharpen our effort, and make us better players. We do these things not because they are easy, but rather because they are hard.

We choose to win Tol Barad.

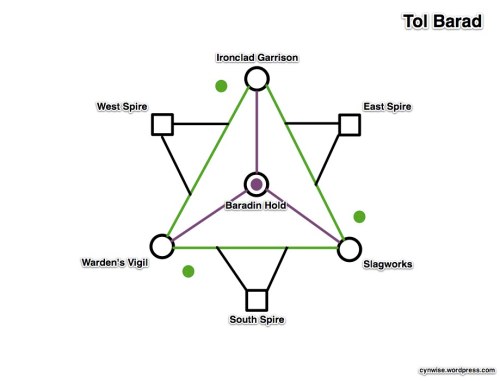

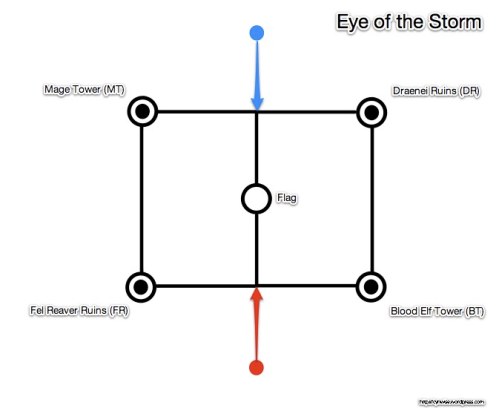

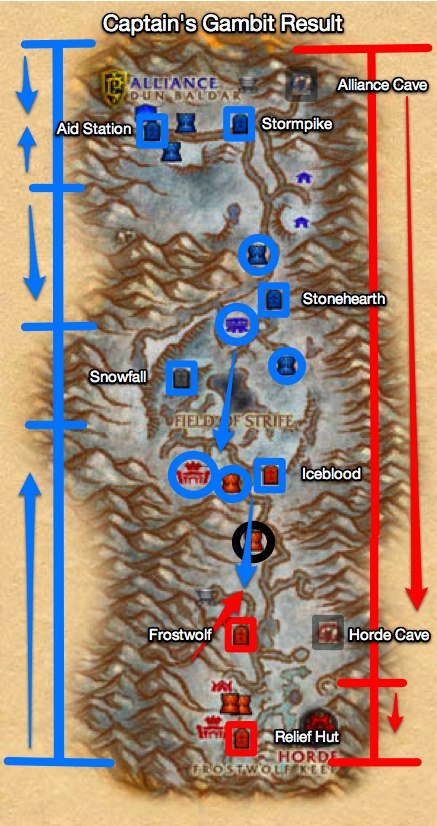

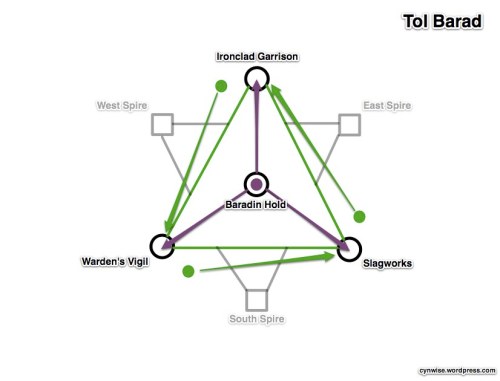

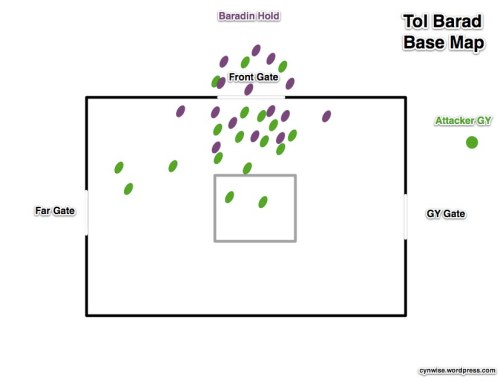

Above is the logical map of the Tol Barad battleground. The objectives for each team are relatively straightforward.

- Attackers: Control all three bases (ICG, WV, Slag) at the same time before time runs out.

- Defenders: Prevent this from happening.

Tol Barad is a battleground of motion and flow. A base is yours when you have more people inside its walls for longer than the opponent. Controlling bases is not about stealth or individual heroics, of elite groups going to capture flags. Defensive control is achieved by letting your troops flow like water from one objective to the next, of overwhelming each node with volume. Offensive control is gained through striking quickly at the right time to disrupt the defensive flow, of seizing the initiative, and of timing the capture of bases just right.

To understand Tol Barad, you must understand how troops will flow. Your troops, your opponent’s troops; in life, and in death. You have to understand both the terrain and the resurrection vectors of where you fight.

If you stand your ground, stubbornly holding onto one node above the others, the battle will flow around you and wear you down until you lose. If you scatter like the wind across the map, you will not have the focus to take any base; disperse, and you will lose.

At any individual base, the attackers have the advantage over time. Attackers who die will respawn close to the base every 30 seconds, about 5 seconds away from reentering the base. Defenders who die will rez back in Baradin Hold, about 15 seconds away from the base.

As a battleground as a whole, however, the defenders have the advantage over time. Defenders who die will respawn 15 seconds away from any given base (the purple lines), allowing them easy access from node to node. Attackers are forced to go around the triangle (the green lines), which takes 35 seconds to go from the front gate of one node to the front gate of another node. If Attackers die and go counterclockwise around the map, the time is reduced to about 25-28 seconds. If they go clockwise, it is increased to almost 45 seconds per move.

The key to winning Tol Barad is understanding the tension between these two fundamental truths of the battleground.

Defenders need to:

- Move as a cohesive unit to establish numeric superiority at a single location.

- Flow troops away from that location when it is attacked to strengthen the next location.

- Delay the attackers as long as possible at each node without reinforcing it.

Attackers need to:

- Move as 2-3 cohesive units to establish numeric superiority at each base.

- Flow troops away from a winning battle to counter the flow of the defense.

- Delay the defenders when they are not at a node; distract and scatter them so they cannot congregate.

If the Defenders can stay together and flow from base to base, they will win.

If the Attackers can disrupt the Defender’s flow and scatter them, while not themselves dispersing, they will win.

DEFENDING TOL BARAD: FLOW LIKE WATER

Tol Barad is heavily weighted towards defense. That doesn’t mean that you don’t have to try on defense, but rather that if you put forth the same effort as the offense, you’ll likely still win. Nothing in life or PvP is guaranteed. This game doesn’t hand you Tol Barad just for showing up.

The simplest form of the strategy is:

- Begin by defending a single base with every person on your team. Everyone on your side goes to that one point until it is attacked.

- When your troops die, you do not reinforce your current base; start moving everyone to the next base instead. Chose the emptiest base to move into. While clockwise motion is slightly more advantageous than counterclockwise (the latter favors the attackers), to you all bases are equal. You can, and should go, counterclockwise if necessary.

That’s it. Flow around the triangle to where your enemy is not, and you will win.

The only people who should not be in the main group are your reconnaissance units: leave one stealther at each base with strict orders to NOT ENGAGE. They are there to count heads, report enemy movements, and nothing more.

You do not need to stay at one base on defense. You can move around the triangle and overwhelm the forces holding each base. As long as you attack with more people – hopefully your entire group – then you will take the base back under your control quickly.

Pay attention to where your dead teammates should be going next. Give clear instructions to dead players so that every 30 seconds you can send a new wave of troops to the correct destination.

- If you are overwhelming a base, have the rezzers rejoin the main force.

- If you are encountering stiff resistance at a base, have the rezzers move against an empty one.

If you are in the graveyard and are not sure where you should go next, ask.

The Defenders should never actively assault 3 bases at the same time. If you leave token forces at 1 or 2 bases, but strongly fortify a 3rd, you cannot be beaten when the weak sites are lost. If you divide your forces equally between all bases, you’ll lose. But you can certainly keep moving forces around and prevent the attackers from capturing any bases – it’s actually quite trivial to shift your forces to make the battleground a 0/3 match if your troops are good at assaulting positions.

Sometimes, you will find yourself down 2/3 bases. The temptation will be to go to the empty base, to reinforce your last stronghold. Resist.

Open your map, and look where all your people are. If they’re already at the last base, then go there. If they’re not, go to where your troops are. The more troops you throw at a different base, the faster you can take it. If the empty base is going down, take a different one.

The attackers want you to overcommit to the wrong base, to confuse you, to scatter your forces.

You have to act like a single unit on defense. If everyone is going to WV, everyone goes to WV and does not stop. No exceptions.

- If you lose focus, you will lose.

- If you lose discipline, you will lose.

- If you stop outside a base, you will lose.

- If you are alone on defense, you are doing it wrong.

- If all you do is sit in a base and wait for 25 minutes, then you will win.

Your defense must flow. It must be unified. It must be reactive.

If you do those things, you will win.

ATTACKING TOL BARAD: JUGGLING FIRE

Assaulting Tol Barad is hard. It’s quite possibly the hardest PvP objective in the game right now. It is easy to give up, to complain it is too hard, to try to cheat the system. This is a place where despair is the greatest enemy your team will face. You can play very well and still lose. You can win every single engagement and still lose the battleground.

You cannot give up.

Taking Tol Barad requires attackers to win the last base faster than they lose another. You must take the final objective quickly, and your defenders must concentrate on holding the falling base tenaciously, to give you as much time as possible to succeed.

This sounds like a simple truism, but in practice it is quite complex. It is akin to describing juggling or riding a bike with words; how hard could it be to keep three objects in the air at the same time, or of falling in two directions at once while pushing yourself forward? These skills are easy to describe, but difficult to achieve the first time.

You will need to win one base faster than you lose another. That’s it. That means:

- You must strike hard and fast as a group. You must surprise the defense and subject nodes to massive attacks, not slow sieges. Trickling troops into a base allows the defense time to adapt and flow; you cannot allow this. It is better to pull back and mass your forces outside a base rather than send individuals to be slaughtered. Waiting the extra 30-60 seconds for a larger group is almost always worth it.

- You must get as many people into a base as possible on the first try. Do not get caught outside, or allow yourself to be drawn out. Do not give chase to defenders fleeing en masse; stay and cap the base quickly while adjusting your forces elsewhere for the incoming assault.

- When defending the base you’re going to lose, stay alive as long as you can. Run away. Go to the back side, don’t stand in front. Use the features of the base to give you line of sight advantages. The longer you survive, the more time you have given your teammates to take the final base. Standing at the front gate and getting mowed down by the zerg might be noble and brave, but it serves no purpose aside from losing the base quicker. Every person in the base slows down the timer. Stay alive.

- Spies are not just for the defense; taking Tol Barad requires knowing where the defenders are going, where they are strong, where they are weak. Defensive behavior is somewhat easier to predict than offense, so spies placed by the central graveyard can indicate where the next resurrection wave is going, while those near the front of the bases can see the approaching troops.

Speed is both your friend and your enemy. You can beat the Defenders back to any given node, but you cannot beat the Defenders to the next node. You cannot circle around counterclockwise in one large group and expect to win. You have to make them go where you want them to go, lead them astray, scatter them, break their zerg. And to do that, sometimes you will have to go fast, and sometimes you have to go slow.

When you hold no bases, taking the first one is your priority. You can feint against all three bases equally to determine where the defense is weak and then shift your forces to taking that base, or pressure on three fronts and see which one you can grind out. The former option gives you a choice to go against a strong target instead of a weak one, which can scatter the defense as they determine where to go next. The latter can be used to gauge enemy strength, as well as your own.

Once you have the first base, you’ve given the defenders a target, which gives you some control over their actions. Be willing to sacrifice that first base if you can take the other two. If the defense is a unified zerg and comes after it, abandon it, split your forces, and take the other two bases. Get out before you are trapped. If the defense is split with some defending and some attacking, split your forces in return and overwhelm their defenses.

The only time you should commit to holding a base is when you are buying your team time to capture other bases. This is one of the paradoxes of attacking Tol Barad; your nominal advantage is in taking a base and keeping it, but since you need to diffuse your forces to hold the captured bases, staying to hold a base can be detrimental to winning the battle. Do not let your forces get trapped defending a base they cannot retake. Move to somewhere useful instead.

Skilled defenders will take advantage of player’s stubbornness and unwillingness to abandon a task to trap your forces in a location they have no hope of taking. If you have 1/3 of your force at ICG, fighting 1/3 of their force but not taking it, or taking it very slowly? The rest of the battleground is still even, but ICG is out of play (and not yours.)

If you are slowly taking bases while attacking Tol Barad, you’re doing it wrong. You have 2 minutes, maybe 3, to take each base. If you can’t, then you need to fall back, regroup, and try again. Try the same place, or a different base – but don’t keep running in from the graveyard to die.

You may need to reset your offensive several times throughout the battle. That’s fine. Don’t panic, maintain the spirits of your team when you fall back to 0/3, and start over again. Resetting the fight is necessary so that your offense doesn’t get scattered. You have to be mindful of falling into several traps:

- Are you chasing the zerg around in a circle?

- Are you hammering on all three nodes with no success at any of them?

- Are the majority of your forces at a single node, yet are not taking it?

- Are your forces all over the map, with very small groups going from place to place?

If so, you need to stop and reset your offense. You cannot win the battle unless you do.

The key to offense is striking hard while juggling fire. You want to strike hard so the defense doesn’t have time to shift and flow around you. You are trying to achieve victory during a fleeting moment in the battle – when the defenders have finally grown weak in their last base, but have not yet taken another one. You need to toss that last torch into the air just before the next one comes down.

Attitude is important. Spirit might (or might not) be useless on your gear, but it’s essential to winning Tol Barad. People all over will have to step up and be leaders. You will have to vocally combat negative feelings and sagging morale when things go against you. Do not let the complainers demoralize your side. You will lose, but when you lose, you will not give up.

You cannot expect to win. You are not entitled to win. The game does not owe you a win. Repeat that several times until it sinks in. Get rid of the idea that you should win. Those thoughts are immaterial to the task at hand. You can play excellently and still lose, just like real life. Get over it. Try harder next time. Grow stronger! The game doesn’t owe you a win.

You must work as a team. Offense requires more coordination than defense. If people on your faction are not participating – afking, gathering, etc. – call them on it. If people are not following with the group – if they’re randomly running around the map – call them on it. If they are dropping raid (and therefore splitting your groups up) – call them on it. Post the afkers in the forums, if you have to, to try to shame them into helping out.

Taking Tol Barad away from the defenders is hard. Really hard. No one is arguing that now.

But that is why we do it.

TAKING A BASE IN TOL BARAD

The best strategy in the world cannot win the battle for you if your troops cannot execute their mission on the ground. Great leadership and communication is all for naught if you cannot do the one thing that Tol Barad absolutely requires: take control of a base away from the opposing team.

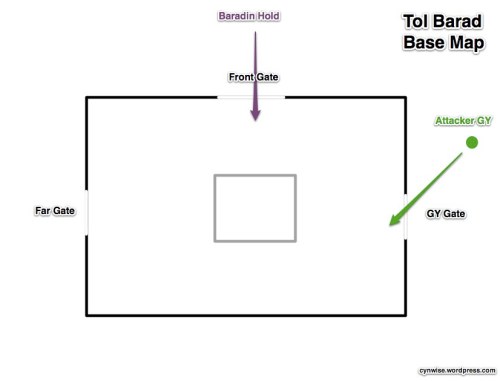

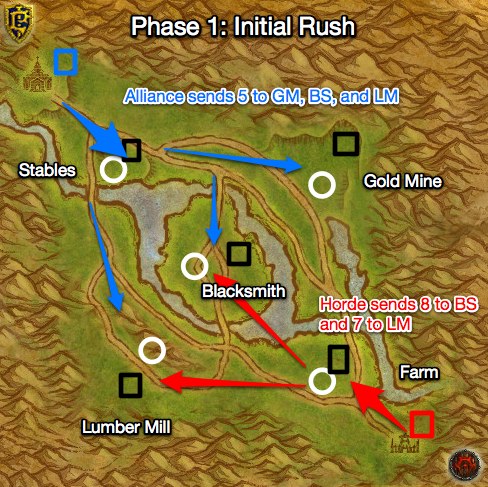

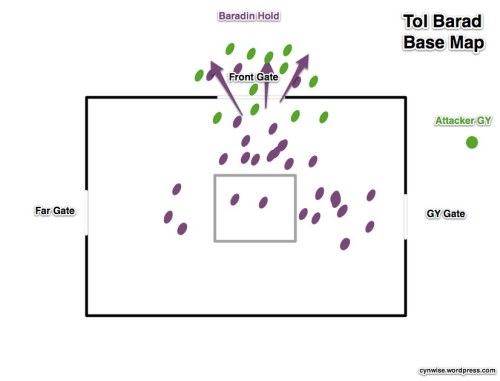

Each base has unique interior features, but the layout is basically the same:

While I can’t comment on what the builders of these bases were thinking, having three gates – maybe they were taking notes from the High Clerist’s Tower – the three gates dominate your strategy in each base, and you can use various tactics to turn them to your advantage.

Let’s look at how Defenders can use the proximity of the Attacker’s GY against them.

The above map depicts the attackers trying to come in through the front gate. The defense is spread throughout the base but sends some strong DPS classes out to meet the rush, maintaining line of sight with the healers. By stunning, slowing, or CCing the incoming attack outside of the base, the attacking players never count towards moving the slider bar. The few attackers who get inside are isolated from their teammates, and while they can cause damage, the attacks are unfocused, unfiltered. At best you might be able to get a few healers down before the attack starts to falter.

The above map depicts the attackers trying to come in through the front gate. The defense is spread throughout the base but sends some strong DPS classes out to meet the rush, maintaining line of sight with the healers. By stunning, slowing, or CCing the incoming attack outside of the base, the attacking players never count towards moving the slider bar. The few attackers who get inside are isolated from their teammates, and while they can cause damage, the attacks are unfocused, unfiltered. At best you might be able to get a few healers down before the attack starts to falter.

The second stage of this defense is to separate the initial assault from the rez waves that will spawn. The attack has been split in two, with a strong central defense between the two.

The second stage of this defense is to separate the initial assault from the rez waves that will spawn. The attack has been split in two, with a strong central defense between the two.

The assault might have a chance, except that the defense is doing the right thing again; forcing the attackers to fight outside the base by engaging them there. Over time, the attackers might be able to mount a good push through the GY gate, but it’s going to take some time – time which favors the defenders.

- When attacking a base, get inside.

- When defending a base, draw the attackers outside.

Let’s look at a different way this base assault could have gone.

By feinting to the front with a decoy, the attackers are able to draw some of the defenders away and out, while drawing everyone’s attention forward, towards the front gate, while they mass at the far gate for a massed charge inside the base.

While it’s tempting to go after the main group of defenders, it’s better to instead establish a presence in the rear of the base. Get everyone inside before the shooting starts, that way you can’t be drawn outside. It also forces the defenders to shift their forces, like so:

Now, while the attackers are still spit, they’ve changed the position of the defenders so that they will have to move away from the GY gate to fight one force, while the rez waves hit them from behind.

Now, while the attackers are still spit, they’ve changed the position of the defenders so that they will have to move away from the GY gate to fight one force, while the rez waves hit them from behind.

The drawback to this kind of assault – besides needing coordination and planning – is that the attackers do not have any way to intercept the defensive rez waves, coming from Baradin Hold. This usually shouldn’t be an issue except during the final battle.

Now let’s look at it from the attackers holding the base.

In many ways, this is a similar layout to the previous example, but the roles are reversed and the sides are switched. It is generally impractical for Defenders to attack from either of the side gates at first, as the front gate is the closest to Baradin Hold’s graveyard. Instead of defending towards the GY gate, attackers should shift their forces to cover an attack from the far gate instead, as their own rez waves will be there later on to intercept the incoming attackers (and keep them out of the base).

In many ways, this is a similar layout to the previous example, but the roles are reversed and the sides are switched. It is generally impractical for Defenders to attack from either of the side gates at first, as the front gate is the closest to Baradin Hold’s graveyard. Instead of defending towards the GY gate, attackers should shift their forces to cover an attack from the far gate instead, as their own rez waves will be there later on to intercept the incoming attackers (and keep them out of the base).

What’s interesting is that the same rules apply – if you want to attack a base, do the unexpected:

Charge the flanks instead of the front, go through the graveyard, and hit the base’s defenders from behind. Reinforcements can then flow in through the front gate, and you turn around and establish a new front at the graveyard gate.

Charge the flanks instead of the front, go through the graveyard, and hit the base’s defenders from behind. Reinforcements can then flow in through the front gate, and you turn around and establish a new front at the graveyard gate.

The supposed advantage of the attacker’s graveyard is only one in terms of time: the attacking force will return to battle faster than defenders. But because that advantage of time requires them to use a set path, it can be turned against them.

This set path is why attackers need to take a base quickly. Drawn out conflicts mean that the majority of the attacker’s force will be coming in from the graveyard, where they can be stopped and overwhelmed.

To sum up:

- Causing distractions at the front gate is good. Assaulting it in force is not.

- Attacking in force on the side away from your graveyard lets you establish better positioning within the base. Within the base means you count.

- Defending a base requires you to meet the opponent outside the base and keep them there. Melee DPS should go out to meet them, ranged DPS should stop them at a distance, and healers should bring up the rear.

- If you get stopped outside the base, getting inside is your priority.

One final word about taking bases: sometimes, your team can’t do it. They may outnumber the defenders but are outgeared; they may be primarily clad in PvE gear against PvP gear; they may just not be very good at PvP. It happens.

What you need to do when your team is outmatched and can’t win the 1:1 matchups is try to reset. Move those people to defense on another node, or have them join a larger assault. Reset the fight and pull them out. You don’t have any real control over who does and doesn’t get into Tol Barad, but you can move them around as needed. If ICG is stuck, have everyone at ICG go to WV – and have Slags go to ICG.

Taking that final base on offense is going to require your best effort. If the team sent in to do the job can’t do it, shift quickly and try something different. You don’t want to get stuck having the same people futilely grind against a base for 15 minutes when it’s the last one to fall.

If you’re defense, though, that suits you just fine.

GENERAL TACTICS

As opposed to strategy, there are some tactical things you can do to help your success in Tol Barad. These apply to both attackers and defenders alike.

Form your raid groups before the battle and assign tasks. Tol Barad can be taken very quickly by a coordinated offense that starts immediately towards their goals. Remember forming the Wintergrasp raids before each battle? Well, there is no reason you shouldn’t be doing that right now. This is something the offense should certainly do, as it gives them the ability to try for a quick win when the battle starts. Send half to Slag and half to WV, and let the stragglers get ICG, and the game is over.

Use guilds to help coordinate team assignments. A guild should be a unit that is already used to working together, and it’s easier to dispatch a guild to do a task than try to assign arbitrary units. Telling the Knights Who Say Ni to go reinforce Slags is more efficient than saying “we need some more over here at Slags!”

Get your side to use PvP addons. Addons like Healers Have To Die, when used by a lot of your team, can help focus your attacks on the primary targets (sorry, healers) and take them down first. Talk up the utility of your favorite PvP addon in Tol Barad general chat.

Use magic to help you move. I’m not just talking about Life Grip (back in base, silly!), Death Grip (out of the base!), and various forms of knockback to bounce people out of the base. I’m also not talking about various creative uses of your warlock teleport circle, or Blink. No, I’m also talking about using the demon TIVO itself – Ritual of Summoning – to move your forces around. Especially in coordination with guilds and preformed raids, this can help move your healers around to get them to the next hotspot before the invasion happens.

You have spies; use them. You should be using spies; stealthed units with the ability to report what they see. Spies in each base can give you troop counts and positioning, as well as join in to take out scouts or healers when your assault comes. Defenders should park someone in each base; attackers might be able to get away with stationing someone in Baradin Hold, but it’s better if the bases are monitored, too.

LEARN FROM YOUR MISTAKES

I spend a lot of time in Tol Barad looking at the above map. What’s going on? Why are we winning? Why are we losing? Where do we need people? Where are we strong, where are we weak?

This is a hard battleground to win as the attackers. The defenders have a somewhat simpler strategy to follow, one that is also more forgiving of individual errors and weaknesses. Go here, now go here. But just because it’s simple for the defenders and complex for the attackers doesn’t mean that the battleground is responsible for your particular loss. Did you have a plan? Did you execute on that plan? Were you able to take the bases you needed to take? Did you stay together, or did you get scattered?

In a normal, balanced battleground, a loss comes down to one team playing better than the other. Maybe you played poorly, maybe they played well – but whatever it was, one team played better than the other.

Tol Barad is different. Tol Barad is biased, heavily, towards the defenders. Winning as an attacker should feel big, because it is big. But it’s not going to happen every time.

Sometimes, you will do everything right and still lose Tol Barad. That’s okay. Don’t beat yourself, or your teammates, up about it. Get over it, learn what you can from it, and try again in two hours.

WINNING AND LOSING

You’re not going to win Tol Barad all the time.

I think that’s the thing that I have learned the most over the last few weeks in Tol Barad – it’s not a no-win situation. This is not the Kobyashi Maru test, a true scenario with no possible way to win.

It’s just hard. Really hard at times, but hard.

At some point, someone on your server will do it. They’ll flip Tol Barad to the other faction. Perhaps they lead a brilliant assault. Perhaps they queue in the late night hours and stay up until the morning making sure it doesn’t switch hands.

Tol Barad is neither fair nor balanced. It is a rock that you can dash your faction against and lose repeatedly. It is a place you can hold for a week and then wonder how you lost in a matter of minutes.

It is not always fun. It is not always rewarding. It is a hard battleground.

But you can win it.

Good luck.